By Farrell J. Chiles

“My father told me us kids don’t understand freedom; all the liberties we have and how we take things for granted,” Ada Hurst said. “He passionately told me he would fight and die for this country again. He never spoke of how he suffered the torture, other than after a while of pain, the brain protects the body and you feel no pain.”

Background

April 9, 2015 marks the 73rd anniversary of the Bataan Death March. The Japanese attacked the Philippines on December 7, 1941, the same day it attacked Pearl Harbor. Three days later, the surprise attack was followed by a full invasion of the mainland of Luzon. By January 2, 1942, the Philippine capital of Manila fell to the Japanese. President Franklin Roosevelt sent a message on February 20, 1942, ordering General Douglas MacArthur to depart the Philippines. On March 11, 1942, General MacArthur left the Corregidor Island by PT boat, reaching the island of Mindanao and from there–flying to Melbourne, Australia. Japanese forces caused the surrender of American troops and Filipinos at Bataan on April 9, 1942. This surrender was the single largest one in the history of American military forces.

An estimated 63,000 Filipinos and 12,000 Americans were forced to march over 60 miles from Mariveles, on the southern end of the Bataan Peninsula, to San Fernando, Pampanga. Up to 15,000 Filipinos and 750 American soldiers died during the march. Survivors were transported by rail from San Fernando to prison of war camps, where thousands more died from disease, mistreatment and starvation. Many survived. Some escaped and renewed fighting until the Allied Forces were able to recoup and later win the war. One such survivor was Pablo E. Gonzales.

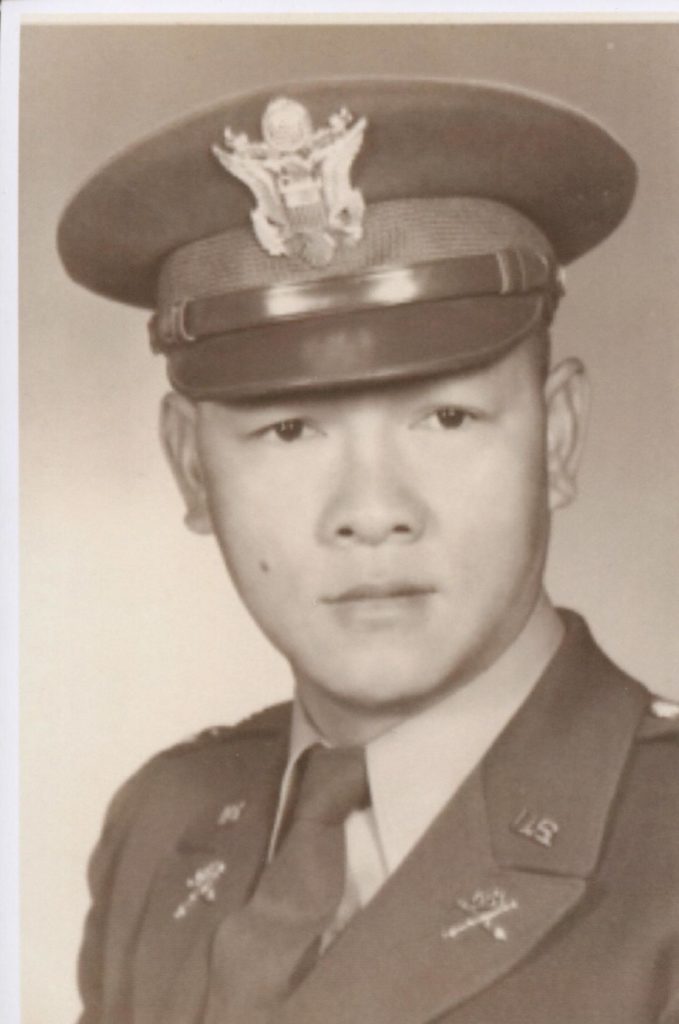

Pablo E. Gonzales

Gonzales was born on January 25, 1918 in Santa Ana, Philippine Islands, near the capitol of Manila. His parents were Cecilio and Lumenada Gonzales. He had two siblings – a brother, Celestino Gonzales and a sister, Constancia. Growing up, Pablo only received a fourth-grade education. He joined the U.S. Army at the age of 19, as a private, on September 18, 1937. On June 5, 1939, he married Cristina Gialon. Their marriage produced five children. During the war, Pablo Gonzales served as a Filipino Scout with Jose C. Calugas Sr., who received the Medal of Honor for his actions during the Battle of Bataan. Gonzales and Calugas both later became American citizens and captains in the U.S. Army.

On December 7, 1941, while a sergeant with Troop A 26th Calvary, Gonzales was stationed at Fort Stotsenburg, Pampanga, Philippines. At 0830 the following morning, commanding officer Captain Gerome McDavitt alerted the base that the Japanese Imperial Army had invaded the Philippines and was advancing on their location.

The following day, Gonzales, along with other soldiers from Fort Stotsenburg, engaged the Japanese at different locations from sugar plantations to bamboo groves. They would fight on the move from different locations every few days, due to Japan’s superior numbers and firepower.

Early on January 6, 1942, Gonzales and his squad were assigned to re-establish severed communication lines. On this day, the Japanese heavy-artillery positions were established. Heavy bombardment devastated U.S. and Filipino troops, causing survivors to scatter throughout the jungles. The last two surviving soldiers in Gonzales’ squad were wounded and taken away. Gonzales remained alone and continued repairing the communication lines. Afterwards, he rejoined another group of soldiers actively engaging the Japanese. During the evening, Gonzales and the soldiers retreated into the jungles.

On January 23, 1942, Gonzales received a Special Order that he was to receive a citation for a Silver Star due to his actions on January 6th. Later, in February, U.S. Army soldiers and Philippine Scouts regrouped and fought the Japanese at Trail 9 Sayaayin Point in Bataan. The Japanese controlled surrounding areas and conducted continual artillery, and bombings throughout the day and night.

On April 9, 1942, Gonzales’ commanding officer, Captain Deruus, ordered his troops to surrender to the Japanese. Gonzales and all the soldiers were taken prisoner and marched to Bagac, Philippines. April 9th was the start of the Bataan Death March, a 60-plus-miles march to San Fernando, Pampanga. On that day of the march, numerous soldiers–especially Americans– were beheaded. Soldiers that were wounded, weak, suffering from heat exhaustion or walking too slow would be bayoneted or beheaded. Every twenty or thirty feet of the road was littered with dead bodies. Japanese officers on horseback would use their Samurai swords to kill prisoners, did so, just for sport. During the march, a Japanese soldier threw a grenade at the prisoners, wounding Gonzales’ legs. As each day passed, bodies along the side of the road increased. On April 22, 1942, Gonzales arrived at San Fernando, Pampanga. Thousands of soldiers who started the march did not make it to San Fernando.

On April 25, 1942, Gonzales and the other survivors were loaded into railroad freight cars and transported to the concentration facility, named Camp O’Donnell in Tarlac. Hundreds of soldiers died enroute. Gonzales, being a sergeant, was assigned to be in charge of a platoon within the camp. Gonzales’ father, Private First Class Cecilio Gonzales, also a Philippine Scout, was assigned to his son’s platoon. On June 2, 1942, Cecilio Gonzales died of illness and starvation.

Gonzales became seriously ill with malaria, beriberi and dysentery. Disposing of bodies became a problem for the Japanese. On September 1, 1942, Gonzales, nearing death from the illnesses was taken out of the prison to die elsewhere. Gonzales, with the help of unknown Filipinos, made it to his mother’s house where she did her best to care for him. Some time during January or February, 1942, medicine delivered by an American submarine from Australia finally cured him of his illnesses.

Gonzales regained his strength and organized his guerilla squad. Under the cover of darkness, they started actively destroying Japanese supply lines on a regular basis. In June, 1943 he was captured again by the Japanese. Suspected of being a guerilla, he was severely tortured. Gonzales convinced them that he was not a guerilla and was released.

During this time, Gonzales stayed in hiding because the Japanese were actively searching for all military and possible guerilla personnel. On September 22, 1944, the American forces returned to the Philippines and conducted the first bombing raids against the Japanese. Gonzales met with the arriving U.S. soldiers and under the command of Major Lapham, joined the guerilla group named BRONCO SQUAD 227.

Gonzales led a guerilla group and obtained intelligence on Japanese movements, combat strengths and conducted small scale harassing attacks. Some of this information was relayed to officers who advised not to attack the Japanese. Believing the Japanese were massing forces at a certain location, Gonzales travelled a distance to personally meet with Lieutenant General A. Carlson, Battalion S-2, 20th Infantry, 6th Army and Captain Chase of the 26th Calvary, Fort Stotsenburg. Gonzales knew Captain Chase from Stotsenburg and had some credibility with him. The information was re-evaluated resulting in a major successful assault against the Japanese.

During the day, part of Gonzales guerilla activity involved integrating into civilian life. He worked as a farmer with his younger brother, Celestino, in Munoz near Manila. The Japanese were always near, but he was always friendly and approached them first. There was one area where the terrain was always flooding. At that location, Gonzales helped push and free Japanese military truck convoys stuck in mud. Along with his fellow guerillas, he would discreetly check to see what kind of weapons and supplies were being transported. Later that evening, Gonzales’ group followed and attacked the trucks for weapons and supplies.

The American troops were now in the Philippines in force and the Japanese were being defeated. On February 25, 1945, Gonzales received orders to report to San Fernando Pampanga 12th Replacement Battalion. On March 4, 1945, he officially became a member of the regular U.S. Army at the rank of Staff Sergeant, assigned to an artillery unit.

Gonzales continued to aggressively pursue the Japanese past the official surrender in September 1945. Japanese troops were still conducting organized attacks, unaware of the surrender. For his actions during combat, Gonzales received the Bronze Star.

After the War

Gonzales, now a Master Sergeant, was commissioned a Second Lieutenant on August 22, 1947. On June 21, 1948, he was promoted to First Lieutenant. Between October 1948 and February 1950, he was stationed in Vienna, Austria, as a general’s aide. In November 1951, Gonzales was stationed at Fort Hood, Texas, assigned to the 27th Armor Field Artillery.

Gonzales again went into combat. He was deployed to Korea during the Korean Conflict and assigned to the 24th Artillery Division. He received his second Bronze Star for actions during combat. On February 24, 1953, Gonzales was promoted to captain and received orders for a three-year tour in Panama, stationed at Fort Davis. He was assigned to an artillery unit, and assisted in the training at the jungle warfare and survival school at Fort Sherman, Panama.

From 1957 to 1959, Gonzales was assigned to Fort MacArthur, California. He was the commanding officer for the 108th Artillery Air Defense. This assignment involved the hidden concrete bunkers along the coast that housed Nike Hercules missiles. He later served as the safety officer with the 100th Air Defense Military Group.

Capt. Gonzales received his Army Retirement Certificate during a retirement ceremony from Brigadier John T. Honeycutt, commanding general of the 47th Artillery Brigade at Fort MacArthur. He retired from the military on May 30, 1959, after 21 years of military service.

His awards and decorations include: the Silver Star; Bronze Star; Army Commendation Medal; Good Conduct Medal; Prisoner of War Medal; Army Defense Medal; American Campaign Medal; Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal; European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal; World War II Victory Medal; Army Occupation Medal; National Defense Service Medal; Korean Service Medal; Philippine Defense Medal; Philippine Liberation Medal; Philippine Independence Medal; and the United Nations Medal.

After Military

Once retired, Gonzales obtained employment working in security positions at the May Company and other department stores. According to his family, those jobs were very frustrating after his successful career in the United States Army. He also found employment with Harbor General Hospital in Torrance, CA and with the Rancho Los Amigos National Rehabilitation Center in Downey, California, supervising a large staff of maintenance workers.

Family

Pablo and Cristina raised five children. The first two, Nor and Zer, were born in the Philippines. Oldest son Nor is an occupational therapist. Zer is a retired Los Angeles Police Department detective. Cecilia is a health care director. Ada is retired from AT&T and resides in Northern California. Paul is in Human Resources at DocMagic, Inc. in Torrance, California.

Nor, the eldest son, remembers Pablo’s belief in spirituality and God. That life is precious. “Dad taught me to care for human life. I remember my father having a picture of Jesus looking up at the sky. My memory of that picture represents Daddy’s belief in God and being optimistic. We went to church every Sunday,” Nor said. “My father was a good provider and would protect his family at all costs.”

Youngest son Paul’s memory is of his father’s love and encouragement. Pablo loved for Paul to play the piano for him and any company that would come to the house. At age 4½, Paul could play anything he heard on the radio. But he couldn’t read music; he played by ear.

“My father’s favorite songs were ‘The Entertainer’ and ‘Fly Me to The Moon’,” Ada said. “Daddy was very proud of that and even though Paul didn’t always want to perform, we did what we were told. Later, as adults, we realized our father was very proud of Paul’s musical ability.”

“When we lived in Lomita, California, we had a huge yard and my Dad grew sugar cane. When we were small, Daddy would find a good sugar cane root, pull it up and skin the root with his machete while gardening, and as a treat, we would chew and suck the sweet nectar from the sugar cane stalk,” she said. “We were outside a lot in our back yard. We had a dog named Spotty, a cat named Pinky and chickens, too. A garden, a playhouse that he built, a swing set, fruit and citrus trees, a shed for tools and a clothes line to hang our laundry,” Ada said. “We had a sandbox, too! We lived there from the time I was born, I think, until I was nine.”

Paul, Pablo’s youngest son, said, “When I was in my early 20s, I recall dad giving me advice about managing people. He had told me that he encouraged his direct reports to give him feedback on how to run the business more efficiently. However, he explained that sometimes you will receive ideas that you know from the get-go will not work. He told me that it is best to respond by saying ‘thanks for your input, I will consider it’, rather than saying “no”. His point of this exercise is that you never want to destroy the “spirit” or camaraderie which, at the end of the day, is the primary goal – to positively impact morale. In addition, you will receive ideas that can be applied. And when this happens, everyone is happy and motivated.”

“My fondest memory is that Mom told me that when I was born, Dad heard music around me. It was pretty much ‘all over for the other kids’,” said Cecilia, Pablo’s first daughter and ‘princess.’ “Even when it was far from the social norm, Dad encouraged me to stretch and just go for it! Whether it was going out to the golf range to hit a few balls or play as many musical instruments as I would like, including the saxophone. Throughout his life, Dad worked on making a difference in people’s lives. Despite being probably the most outgoing of my siblings, much like Dad, I am painfully reserved about the lengths that I and my siblings will go to take care of people – getting them out of harm’s way, meeting needs and handling them with utmost respect,” she said.

“I learned discipline, integrity and being a gentleman from my father,” Zer Gonzales said. Displayed on the walls of his home in Southern California is his father’s military shadow box, exhibiting his awards and decorations. Also on the wall, in a case, are 12 bolos knifes (similar to machetes) and Kris daggers from Pablo’s days during World War II. He also has a case displaying four Samurai swords that his father confiscated from Japanese soldiers.

Cristina Gonzales died on October 7, 1980. Pablo Gonzales died of a stroke on February 28, 1993. They are buried together in Green Hills Cemetery in San Pedro, California.

Pablo Gonzales was a Bataan Death March Survivor. He is a Filipino hero. He is an American hero. He left us with a proud legacy.

_______________________________________________________________________

Farrell J. Chiles is the author of “African American Warrant Officers…In Service to Our Country”. He is a member of the Military Writers Society of America (MWSA). Chiles resides in Phillips Ranch, California. He can be reached at farrellchiles@yahoo.com.